FLOREPHEMERAL

2022-2024

“In the first, microbial, stages of evolution, all species had the same life. They shared the same body and the same experiences. Everything we are now – whether we are an elephant or an oak, a lion or a mushroom – was concentrated in that same life which first detached itself from silent matter. For billions of years, this life has been transmitted from body to body, from individual to individual, from species to species, from kingdom to kingdom.”

Emanuele Coccia, All Species Have the Same Life, GRANTA Magazine 151, April 2020

Humans have spent all of history seeking what, if anything, defines us—what separates us from the rest of the natural world. First it was the soul, then intelligence, then sentience, among many other hypotheses; each one murkier than the last. One by one, philosophers have unraveled these distinctions until the only one left standing was the quest of exceptionalism itself. The stubborn idea that we are apart seems to be the only thing that actually sets us apart.

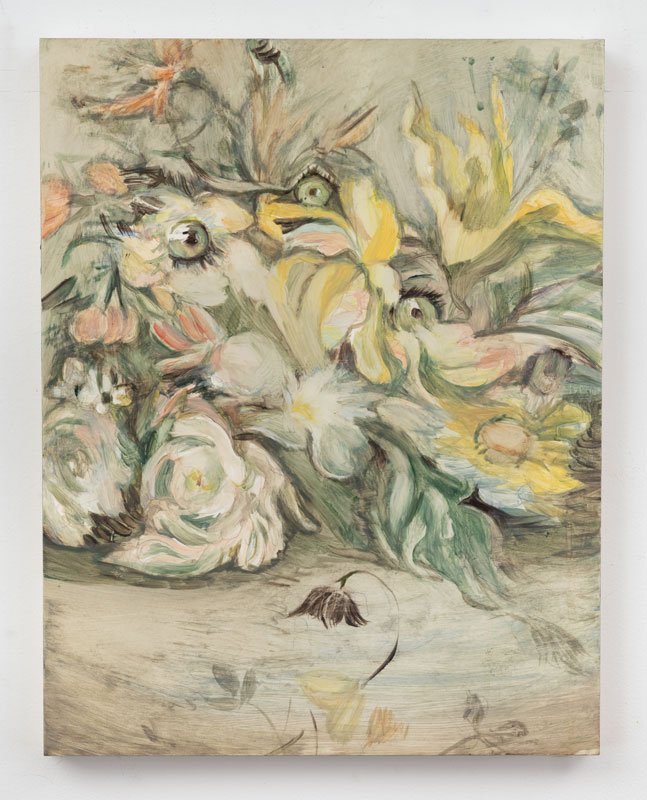

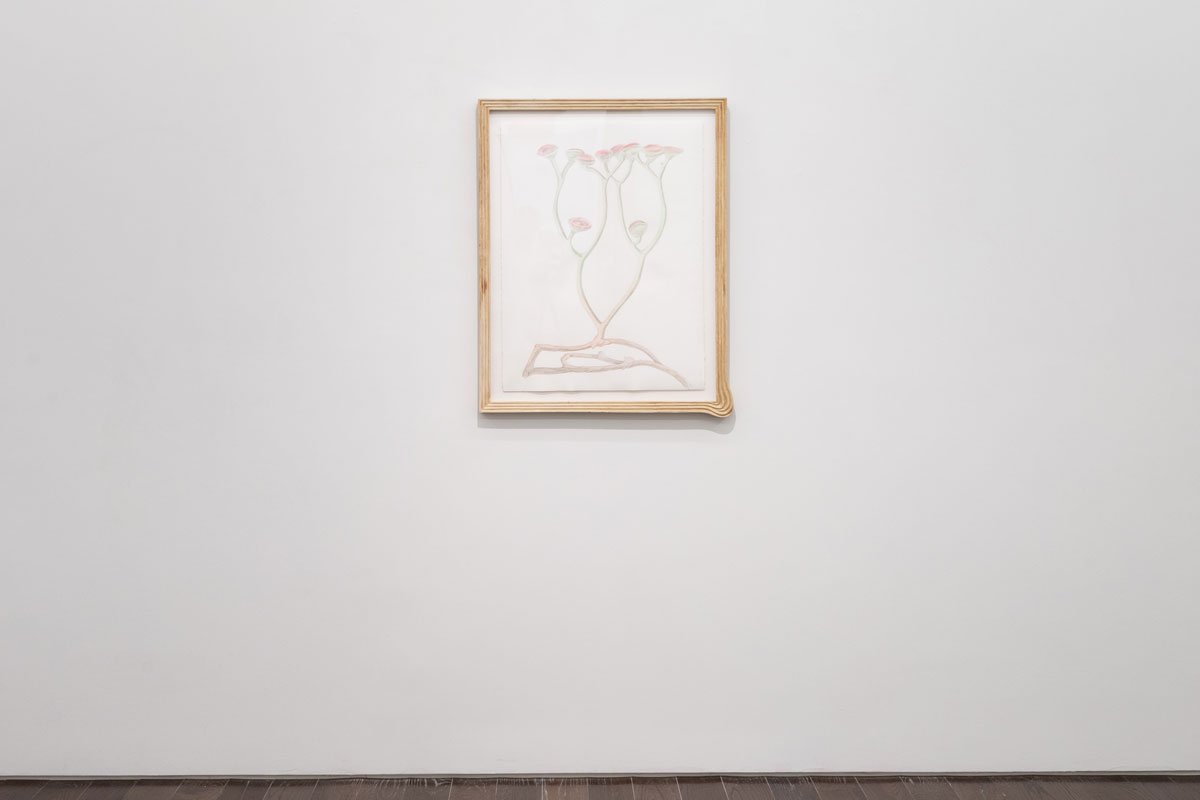

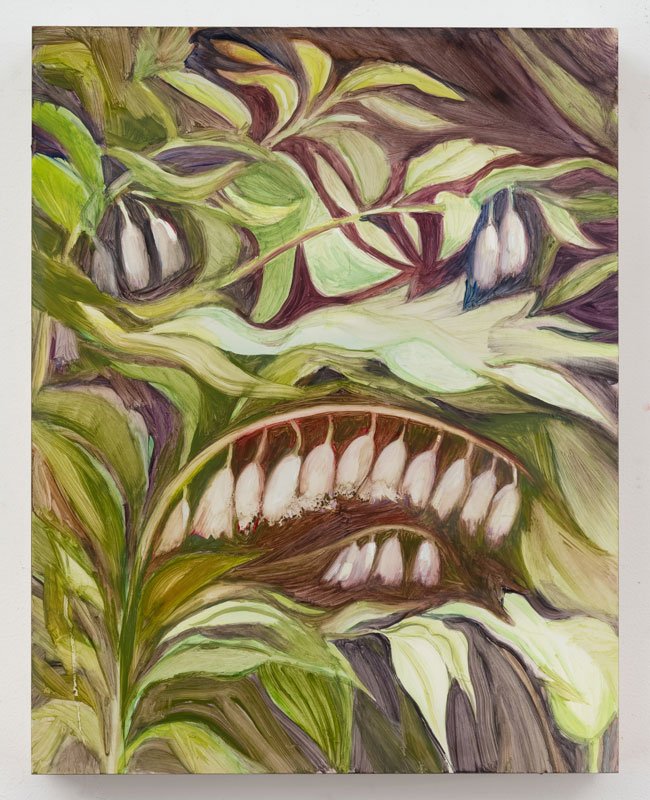

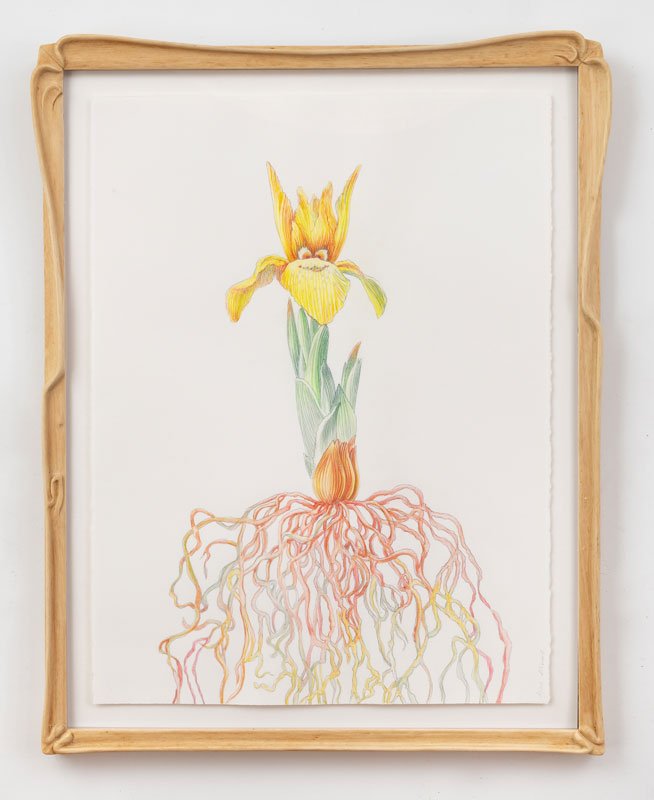

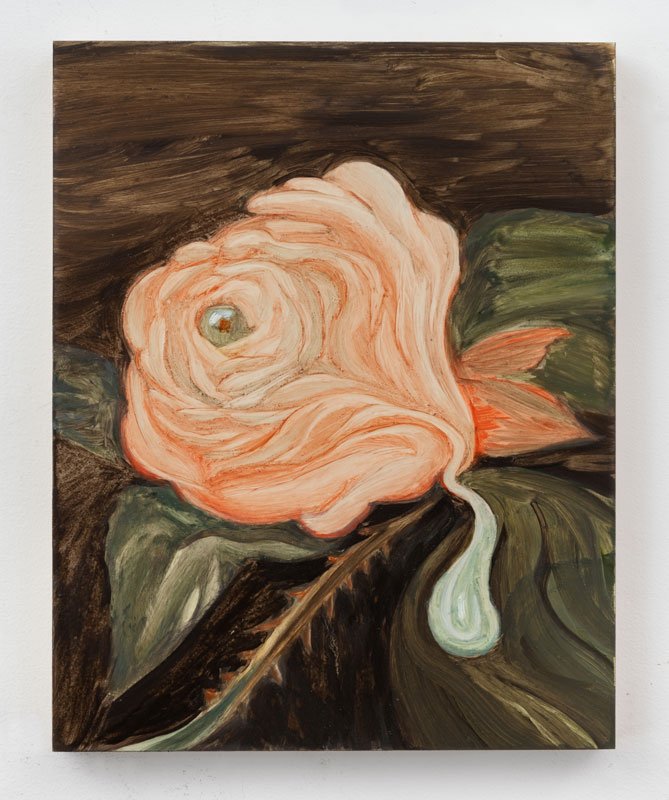

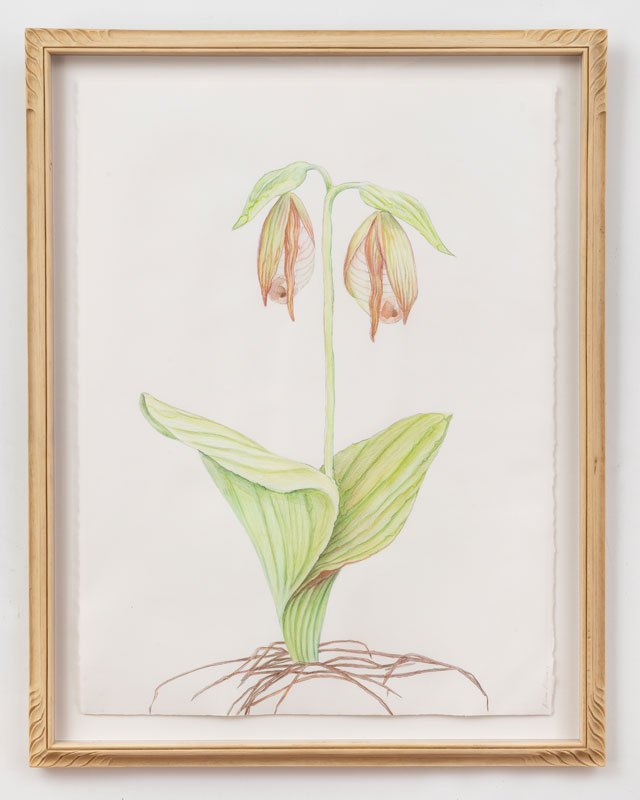

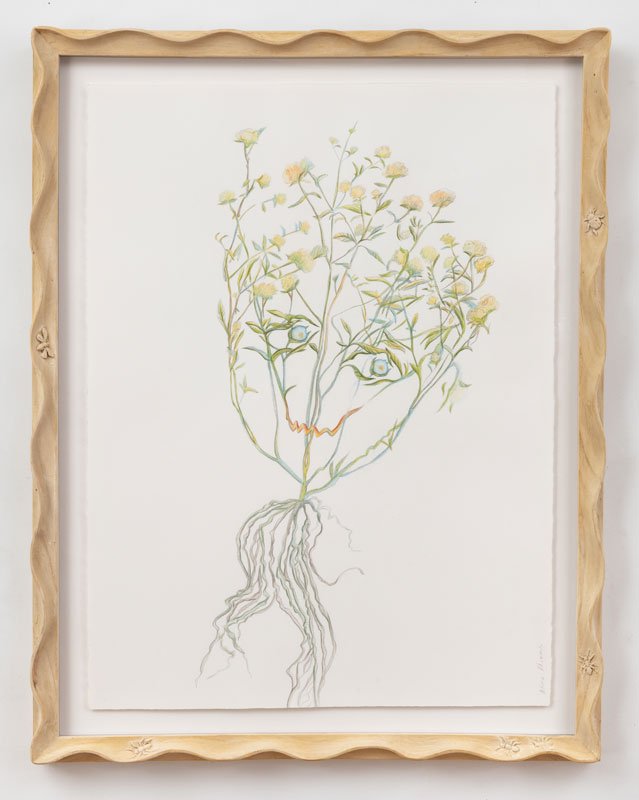

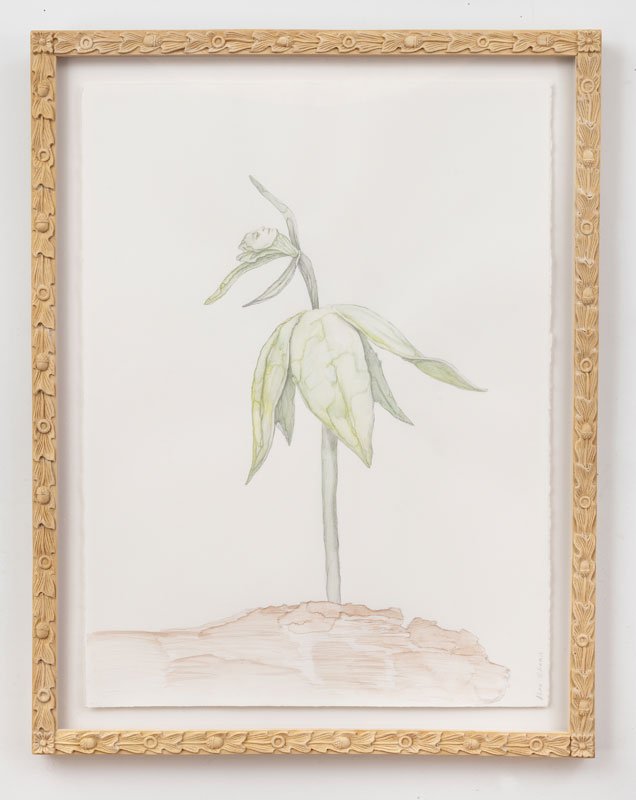

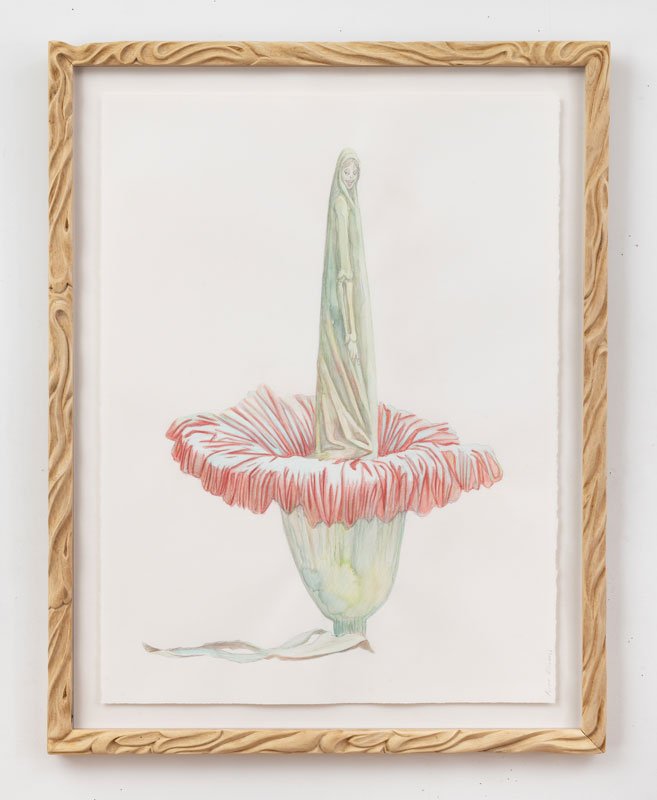

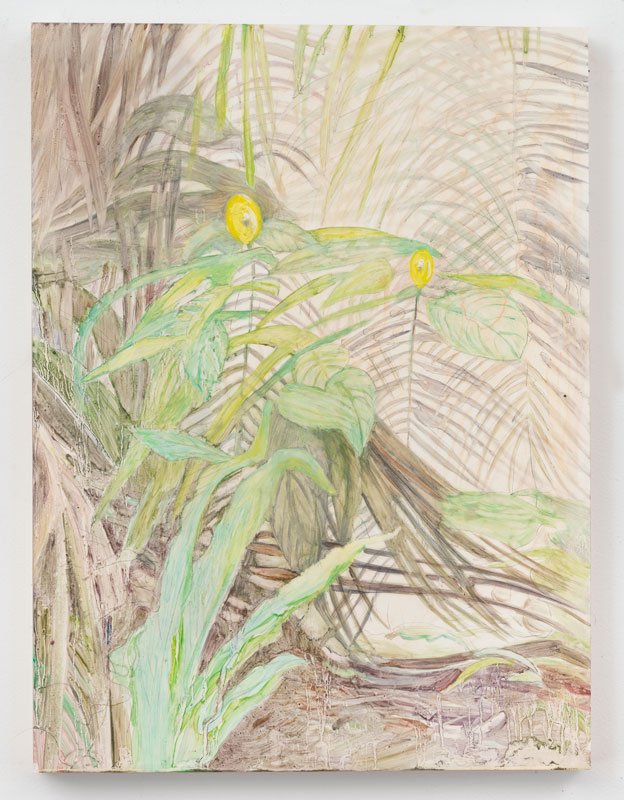

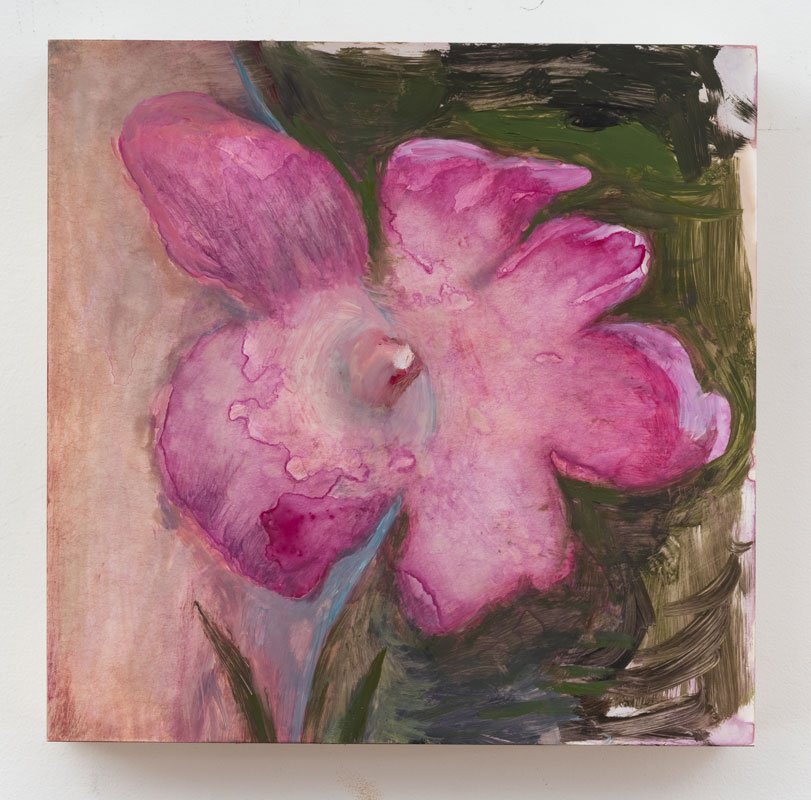

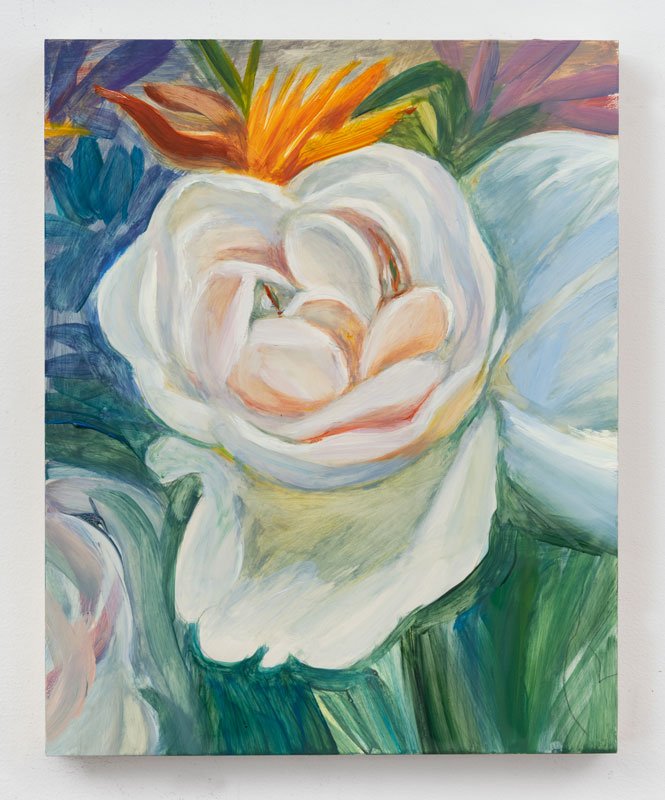

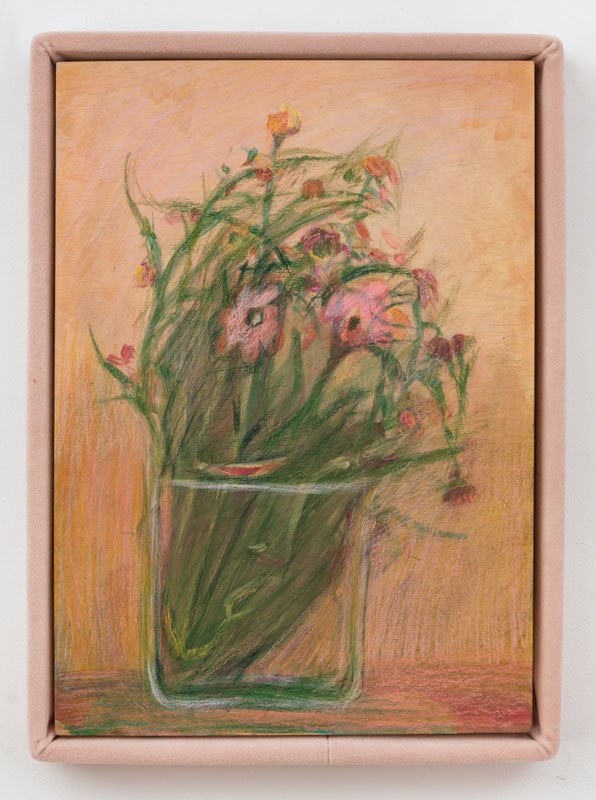

In her Endangered series, Alina Bliumis joins a discourse which challenges this impulse all together and asserts that the fundamental quality of life and the history and evolution of humanity is intrinsically linked and intertwined with the fate of the natural world. This series of watercolor drawings, which the artist began in 2022 features sixteen portraits of endangered and extinct flowering plants in custom, hand carved wooden frames. The series will be accompanied in the show by a group of small painted floral portrait studies made by the artist for the exhibition. The term ‘portrait’ here is used in earnest, as the works—which initially may appear to be botanical drawings—actually reveal hidden faces and anthropomorphic features. By turning the flowers into figures, Bliumis subjectifies the plants and asserts the individuality of their stories.

The stories, which often come from indigenous folktales from the plants’ countries of origins, frequently center around mystical or healing properties of the plants. These properties have made them particularly subjected to over-harvesting by humans. In combination with the perilous effects of climate change and the destruction of native wildlife habitats, the overuse of these plants has led to their endangerment and extinction. At first, this news hits differently than, say, the news of the extinction of an animal species; however this is only a function of our perceived distance from the plants. Our empathy wanes the further we are on the tree of life. This is where Bliumis’s imperative comes into play. If we can bring these plants closer, make them more familiar, and tell their stories, can we internalize our shared fate? Can we potentially correct the courses of their species or pay proper respects to those we have already lost?

The assertion of the plants’ subjectivity and their demand for respect is also emphasized in the individualized hand carved frames surrounding each piece. While traditional botanical drawings have typically been kept in folios or appeared as plates in books, carved wood frames are associated with royalty and portraiture. The frames themselves often include details that emphasize the characteristics and personalities of each flower. The rippling fabric-like texture of the Corpse Flower is mimicked in the folds carved into the wood. The delicately windswept Turquoise Ixia is surrounded by fluid waves. The Queen’s Lady’s Slipper’s frame seems to crown the flower in forms that follow the shape of her petals. With extreme care, the artist draws each frame’s design exactly to scale before sending the designs to made by hand by master wood carvers. There is a poetry also in insistence on keeping dying art forms like hand carving alive. Again, the future of the flower and our own futures become intrinsically linked.

Florephemeral is an invitation to see ourselves in creatures so othered that they feel totally apart from us. It is an invitation to invest in their, and our own, protection. If in these flowers we can see humor, grief, history and play, then we may finally understand how very closely we are tied to nature and how—in writer Emanuele Coccia’s words— “everything we are now…was concentrated in that same life which first detached itself from silent matter”.

Francesca Pessarelli, February 2024